Lee el artículo de Gabriela Camacho y Paolo Sosa, escrito para Foreign Policy ► https://bit.ly/3rdfhjl

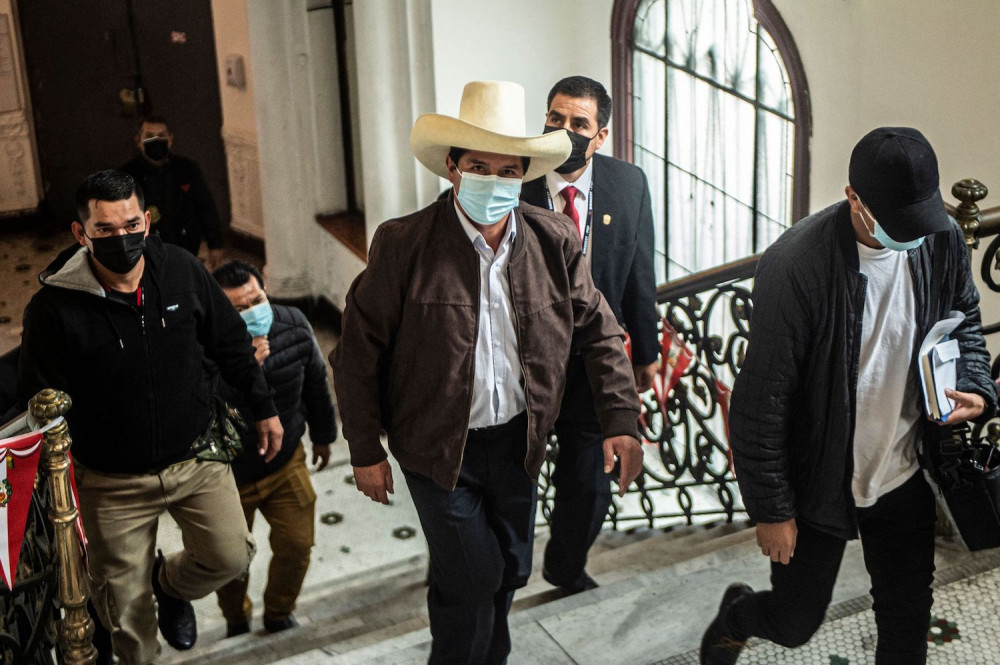

FOTO POR: ERNESTO BENAVIDES/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Peru’s longest period of democracy yet is in danger of coming to a painful close. Over the past few years, politicians have engaged in near-constant takedowns of opponents—including impeachments and judicial targeting—and obstruction of governance. This has contributed to the public perception that democracy is not working, either because it does not produce concrete results or because all politicians are corrupt. Unsurprisingly, a large percentage of voters in general elections this year chose populist, anti-system candidates from all sides of the spectrum. In the end, the two candidates who made it to the presidential runoff barely got 33 percent of the vote during the first round. As in previous elections, a significant group of Peruvians simply chose to leave their ballots blank; yet this time, blank votes were the second “most voted” option.

On July 28, a new president will take office. Pedro Castillo—a leftist candidate who proposed to “deactivate” important democratic institutions, such as the Constitutional Court and the Ombudsman’s Office—defeated right-wing Keiko Fujimori, a candidate beset by numerous corruption scandals who is the daughter of former Peruvian dictator Alberto Fujimori, by less than 1 percent of the votes in early June’s runoff election. Although both are populist and socially conservative, they have entirely different views on the economy and the role of the state.

An important portion of the electorate feared this outcome, concerned Castillo might concentrate power and go down an authoritarian path—he has made statements indicating openness to shuttering the legislature should it oppose his suggested economic and political reforms. He also has shown the necessary charisma and will to go against democratic institutions. But recent history points toward ungovernability rather than authoritarianism. Peru’s Congress remains fragmented, and Castillo’s party does not hold a majority. Castillo’s own priorities have become somewhat unclear as he moderated his previous statements and altered the party’s platform between the first and second rounds of the election.

Either way, the next few years may see further democratic erosion—and will almost certainly see an elite backlash against Castillo—while policies to improve Peruvians’ standards of living fall by the wayside. This is not a new problem. Since 2016, Peru has faced similar governability crises. The ongoing clash between the executive and legislative powers has created four presidents in a period of just five years. In part, this is because of the elites’ irresponsible behavior—who recklessly prioritize their own political and personal agendas and use all constitutional and judicial mechanisms available to them to pursue their political enemies, eroding public trust in institutions. In five years, Peru has experienced the resignation of a president, a closure of congress, a call for early elections, a presidential impeachment (accompanied by multiple impeachment attempts), and the preventive imprisonment of the country’s main political leaders.

Such extreme decisions have pushed Peru’s fragile institutions to a breaking point. Peru not only has one of the highest per capita COVID-19 death tolls in the world but has also experienced a corresponding economic downturn. Although citizens were concerned with managing their economic situations and addressing the pandemic, the political elite was focused on attacking one another. Congress’s decision to remove former Peruvian President Martín Vizcarra at the end of 2020, accusing him of corruption in charges that many considered politically motivated, was the straw that broke the camel’s back, fueling massive protests across the country.

Five years ago, then-right-wing Peruvian President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski defeated Keiko Fujimori by a small margin. In retaliation, the Fujimorista majority in Congress boycotted the government’s initiatives and aimed to censor its ministers. Ultimately, they promoted Kuczynski’s removal based on his alleged links to the Lava Jato (Operation Car Wash) corruption scandal, an investigation that ultimately revealed bribery and money laundering across the region. As a result, the president forcibly resigned in 2018 after videos alleging a vote-buying negotiation to avoid the first impeachment attempt were made public. Then-vice president Vizcarra thereby replaced him. The scandal gave the perfect excuse for the opposition to continue attacking the government. Months later, Keiko Fujimori herself was detained for several months, allegedly linked to the Car Wash scandal.

As Peru began to experience the effects of the Lava Jato investigations—which have taken down politicians across the region—party leaders, congressmen, and any politician with a chance of running for office quickly pointed blame at one another. Most political leaders supported the indiscriminate use of pretrial imprisonment against rivals to achieve political advantage (and electoral gains). In this context, Vizcarra secured popular support by using an anti-corruption and reformist agenda he claimed was impossible to advance given the presence of a disloyal opposition: Fujimorismo. He was likely right, but his decision to use an institutional arrangement to close Congress in 2019 and call for early legislative elections, which took place in early 2020, did not help bridge the political crisis or improve public perception in the long term. Although the measure was initially popular, the result was more tension between the executive and legislative powers once the new Congress was installed, which led to further political alienation among Peruvians.

That alienation is rooted in recent history. Since Peru’s return to democracy in 2000, after the fall of Alberto Fujimori’s regime, the economic elite has been imprudently reluctant to allow gradual economic and social reforms, defending extreme austerity policies at the cost of popular demands for change. Between 2001 and 2016, Peru was successful in reducing poverty but failed to expand social programs to reach much of the population, leaving them vulnerable to any sudden change of the economic tide.

Last year, the pandemic drastically exposed these limitations as 3 million Peruvians slipped back into poverty. The economic model keeps failing them. In the second round of the 2021 elections, the southern and central parts of the country’s Andes regions, with high levels of poverty, massively supported Castillo’s radical change proposal. This was unsurprising: Peru has a socioeconomic divide along territorial lines that has never been fully addressed by any group in power, leaving many voters in rural regions unheard for decades.